From the Mind of a Woman

For many Americans, World War II was a distant thought until the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. However, for U.S. Representative Edith Nourse Rogers (Mass.), the looming likelihood of U.S. entry into the war spurred an idea that would forever change the role of women in the armed forces.

Rogers, recalling the involvement and treatment of women during World War I, saw the opportunity to provide much needed opportunities, support, pay, and protection for women offering to serve their country. Unlike during the First World War, Rogers was determined to make it possible for women to receive the same legal protection as their male counterparts. As a result, she proposed the creation of an Army women’s corps (separate from the existing Army Nurse Corps).

Despite opposition from both the U.S. Army and Congress, the bill which Rep. Rogers introduced in May of 1941 garnered attention and reconsideration after the December attack on Pearl Harbor. Heralded as an opportunity for women to “free a man for combat,” the bill met fierce opposition in Congress – chiefly among southern male delegates who contended that women belonged in the homes cooking, cleaning, and raising children. Some, along with several newspapers, even argued that, with the women overseas, there would be a drop in the birth rate (a hotly debated topic when it came to light that members would be discharged should they become pregnant).

Nonetheless, the need for soldiers and support staff was overwhelming and, by May of 1942, Congress approved the creation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). Not wasting any time, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law the next day and Oveta Culp Hobby was sworn in as the corps’ first director.

Led by a Woman

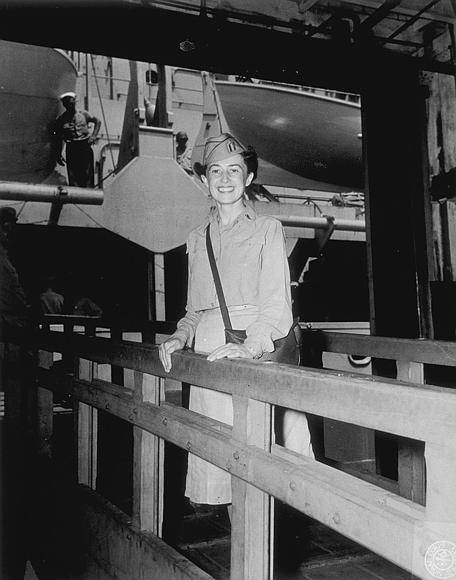

With ten years experience as an editor for a Houston newspaper, five years as a parliamentarian in the Texas legislature, the author of a book on parliamentary procedure, and the wife of former Texas Governor William P. Hobby, Oveta Culp Hobby was a stellar candidate for the first director of the WAAC. Her own credentials made her a standout in a largely traditional era and her experience in politics alongside her husband had rendered her adept at navigating the waters of local and national politics. With strength and smarts, Director Hobby weathered everything from open condemnation of women in the armed forces to more subtle and frequently sexist questions aimed at whether the women involved would be allowed to wear makeup or even what color their uniform underwear would be.

Despite these unsettling questions and jabs from political opponents, the WAAC hit the ground running with more than 35,000 applicants from all over the country vying for less than 1,000 positions. The requirements for applicants included the following:

- Applicants had to be a U.S. citizen between the ages of 21 and 45 with no dependents.

- Applicants had to be at least five feet tall and weigh 100 pounds or more.

The quality of applicants, beyond the basic requirements, became clear early on. Interviews conducted by the press revealed that the average WAAC officer candidate was roughly 25 years old, had attended college, and was working in an office or educational setting. In less than two months, the first class of WAACs were selected and on their way to training camp and Officer Candidate School.

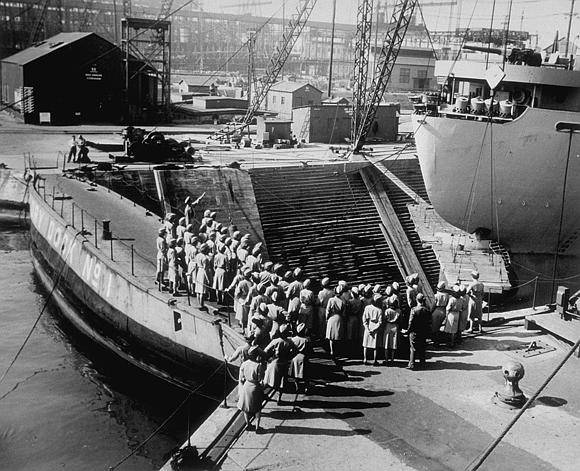

This first class of WAAC officer candidates arrived at Fort Des Moines in Iowa on July 20, 1942. As the first WAAC Training Center, the fort welcomed 125 enlisted women and 440 officer candidates (40 of whom were women of color). These candidates offered the U.S. not only its first view of women in the armed forces, but also its first view of women of different races being trained together.

Made up of Women

Initially, women worked in positions such as baking, clerical, driving, and medical work. But, over its first year, more than 400 jobs became open to women. As more and more of these women took on new roles for their country, they found work as weather forecasters, cryptographers, radio operators, sheet metal workers, parachute riggers, aerial photograph analysts, control tower operators, mechanics, and so much more. Their value became clear to many both within the WAAC administration as well as within some sections of the Army (most notably the Army Air Forces or AAF).

But, the fact remained that, despite Rep. Rogers’ goal of providing equal protection and treatment for women serving their country, noticeable inequities persisted. For instance, the bill which created the WAAC did not prohibit women from serving overseas, but it also failed to provide them with overseas pay, veterans medical coverage, government life insurance, and death benefits. Similarly, the ranking systems between the U.S. Army and the WAAC illustrated further inequity. Not only were women not allowed to command men, but they were also paid less than men in equivalent rankings.

Nonetheless, approximately 150,000 women served in the WAAC (later known as the WAC or Women’s Army Corps) during World War II. Operating both on the home front and overseas, WACs arrived in New Caledonia, Australia, and even on the Normandy beach head while still more served in the regions of China, Burma, and India.

For many of these women, they served for their country, for their families, for their communities, and for themselves. As the first women (other than nurses) to serve within the ranks of the U.S. Army, they pioneered the involvement of women in the U.S. armed forces. Made up of women from multiple races and ethnicities, the diversity of this often unsung group of servicewomen along with its origin, management, and work at the hands of women set it apart in U.S. military history.

Activity #1: WAAC/WACs at Home

Although the first WAAC Training Center was in Des Moines, Iowa, other training centers were created in these locations as well:

- Daytona Beach, Florida

- Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia

- Fort Devens, Massachusetts

Look into how far away each of these locations are from your home. Which of these four training centers would be closest to your area? Do you know of any other WAAC or Army field installations that were near your area during World War II?

Activity #2: WAAC/WAC Work

Although some of the early jobs assigned to WAAC/WACs were baking, clerical, driving, and medical work, later on women had the opportunity to work in many other fields. Which of these would have been most interesting to you? Why?

- Weather forecasting

- Cryptography

- Radio operation

- Parachute rigging

- Bombsight maintenance

- Aerial photograph analysis

- Control tower operation

- Mechanics and vehicle repair

Activity #3: Women’s Month

Do you know much about Women’s Month? Try looking into your area’s local women’s history! Stumped and don’t know where to start? Try answering some of these questions:

- Are there any programs, organizations, or businesses in your area that have been founded or run by women?

- Are there any buildings, parks, or sites named after local prominent women in your area?

- Are there any projects in your area focused on celebrating women’s history?

Throughout the month of March, you can learn more about Women’s Month and the ways that people are celebrating it by following #nationalwomensmonth or #womenshistorymonth on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter!

Did you learn about WAAC/WAC history or women’s history in your area this week? Did you discover something new about Women’s Month? There are countless stories that come to light every year about the amazing roles that women have played in communities around the world! So, in honor of these women, celebrate Women’s Month by remembering that Women’s History is American History!

Share your activity results with us on social media by tagging History Becomes You and by using #historybecomesyou !

Check back next week for the next of many peeks into history as we continue to celebrate National Women’s Month!

love the articles. keep them coming please..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! More are on the way!

LikeLike