Public Memory

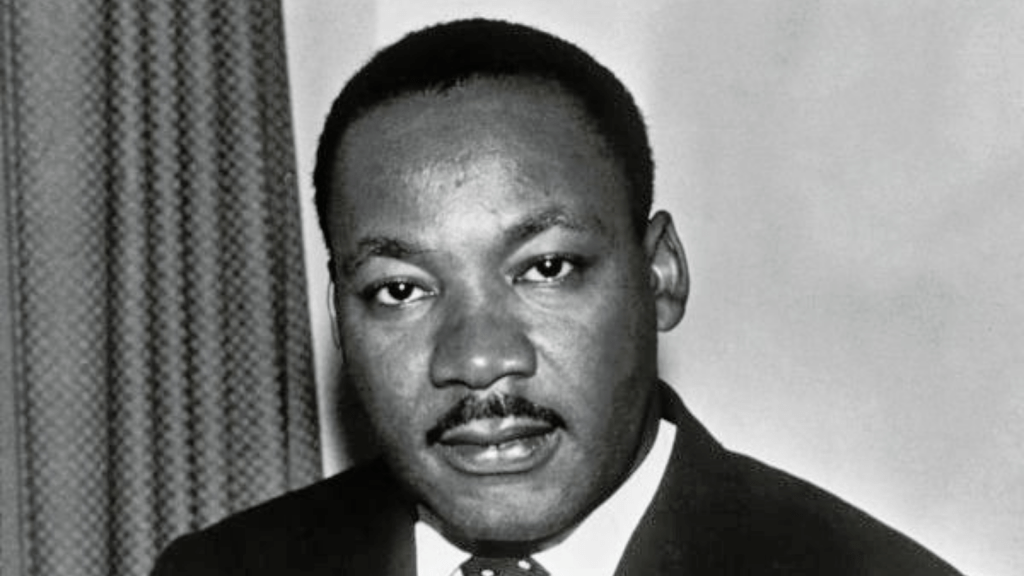

For many of us throughout the United States, the celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day can take on many different forms and meanings. On a basic level, it celebrates Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday, but on a much larger level, it also celebrates Dr. King’s achievements during the civil rights movement as well as the achievements of thousands of civil rights activists from all walks of life.

But, as with most commemorations in history, Martin Luther King Jr. Day also reminds opponents of the civil rights movement of the ways in which the events of the 1960s painted their home states in a light of racism, segregationist policies, and violence. In some cases, Martin Luther King Jr. Day is grudgingly acknowledged, while in others it has been enveloped within other commemorations. Most notably, in Alabama and Mississippi (two states still known for civil rights abuses during the 1960s), a joint celebration known as “King-Lee” day has served as a celebration of both Dr. King and Confederate General Robert E. Lee – an unexpected and seemingly opposing pairing of historical figures.

Similarly, Virginia observed Lee-Jackson-King Day until 2000 – including another Confederate leader, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, in the celebration. Although the state went on to separate the commemorative days and, ultimately, eliminated Lee-Jackson Day, for many, these joint commemorations conjure up questions about how far the country has come over the course of the last 60 years.

Reading Between the Lines

As a public school-educated student, I was fortunate to have been taught by a series of amazing and dedicated teachers. I was taught to question the prevailing storylines of history, to look at historical events with new perspectives, and to work to understand the entirety of historical figures rather than the idealized versions that have become memorialized (often quite literally in stone or metal).

So, with my arsenal of amazing educators, I was surprised to find that my education had a glaring hole in it in the shape of Martin Luther King’s presence in St. Augustine. Although I had learned about the civil rights movement and about Dr. King’s involvement, the events always felt like they took place at a great distance – somewhere in Mississippi, Alabama, or Tennessee. The closest that it seemed the civil rights movement had come to me and where I had grown up was in the form of individual protests scattered throughout the state – wade-ins at public beaches, swimming in segregated pools, requests for service at segregated businesses. But somehow it never came up that Martin Luther King had spent time in Florida.

My shock at this glaring gap in my knowledge about such a well-known movement reminded me of the work that is still being undertaken to properly honor and understand the Civil Rights Movement and those who took part in it.

So, in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I want to share with you the story of the 1964 civil rights campaign in St. Augustine, Florida.

A Most Law-Less Community

In the days, weeks, and months leading up to the 400th anniversary of St. Augustine’s founding, Florida’s politicians and business owners hoped for a positive portrayal of one of the country’s oldest cities. Instead, the media captured a rapid succession of protests, demonstrations, and attacks all centered around racial tensions and segregation throughout the city. The rapidly approaching anniversary meant that the eyes of the nation would be on St. Augustine and, for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leaders, this meant that it was the perfect stage to call attention to the racial injustices and inequality that thousands of citizens were experiencing under segregation and Jim Crow laws. According to a June 5, 1964 news article in the New York Times, Dr. King and the SCLC had chosen St. Augustine as a focal point of the 1964 summer campaign saying, “We are determined this city will not celebrate its quadricentennial as a segregated city.”

So, far from the tourism photographs of glittering beaches or historic architecture, images appeared across the nation of motel owners pouring acid into segregated pools, civil rights leaders examining bullet holes left by would-be assassins, and night after night of peaceful protests turned violent from attacks by angry segregationists and white supremacists. These events and images marked St. Augustine as a city that refused to end racial injustice even 400 years after its founding.

Called “the most law-less community he had encountered,” Martin Luther King saw the potential to advance the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through the movement’s efforts in St. Augustine. But he was continuously taken aback by developments in this northeastern corner of Florida. Not only had he been monitoring the escalating tension in St. Augustine over the course of 1963, but Dr. King also wrote to the White House to question the use of federal funding for the city’s 400th anniversary in the face of rumors that the St. Johns County sheriff, A. L. Davis, had recruited special deputies to handle “racial trouble” from the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan.

Arriving himself on May 18, 1964, Martin Luther King experienced much of this violence and unrest first hand. Speaking at a local church on May 27th, his presence garnered a great deal of unwanted attention and led to an early morning shooting at a small house at which he was staying just two days later. Threats on his life and multiple arrests made it clear to Dr. King that St. Augustine was as vehemently segregated as many of the other more well-known cities in which he and his fellow activists had worked.

Throughout June 1964, King and SCLC leadership continued to organize sit-ins, evening marches to the Old Slave Market, and wade-ins. While violence continued to escalate around these peaceful protests and hundreds of activists were arrested, King continued to appeal to the federal government and the White House to step in and pressure prominent white citizens to negotiate with the movement. But, rather than improve the tensions within St. Augustine, on June 18, 1964, a Grand Jury called on Dr. King and the SCLC to leave St. Augustine for one month to diffuse the situation. The Grand Jury claimed that the presence of the activists had disrupted the “racial harmony” of the city – a claim the Dr. King and SCLC leadership called immoral and false as they insisted that St. Augustine had never had anything approaching peaceful race relations.

Yet, as SCLC lawyers began to win court victories in St. Augustine under Judge Bryan Simpson against the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations, the coverage of the tensions and protests in Florida were helping the Civil Rights Act to wind its way through the Senate. When Florida Governor C. Farris Bryant announced the formation of a biracial committee to restore interracial communications in St. Augustine, the SCLC was willing to leave the Sunshine State and continue their efforts elsewhere in the south. However, in spite of the passage of the Civil Rights Act in July 1964, constant threats and picketing by the Ku Klux Klan kept many in St. Augustine too intimidated to integrate. In the face of these continued threats and acts of intimidation, Dr. King observed that the violence and brutality that the St. Augustine community had endured had helped to prompt Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 even though they continued to face segregation at home.

“Let us recognize that violence is not the answer. Hate isn’t our weapon either. I’m talking about a love that is so strong that it organized itself into a mass movement and says somehow, ‘I am my brother’s keeper and he is so wrong that I am willing to suffer and die, if necessary, to get him right.'”

Martin Luther King, St. Augustine, Florida (1964)

St. Augustine represents one of hundreds of stories of the Civil Rights Movement that we can still learn from today. And, although the city of St. Augustine has made progress, it continues to represent the changing attitudes towards Dr. King and the commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. St. Augustine eventually grew from a city where some people had once hated Dr. King’s presence to a place where people gather annually to celebrate the work of the Civil Rights Movement. It would have been unthinkable to those in power in 1964 St. Augustine, but today, people celebrate the places that Dr. King visited, stayed, and preached.

Activity #1

In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, check your local news stations to find ways that people are celebrating the Civil Rights Movement in your area. Are there readings of Dr. King’s speeches? Are there commemorative marches? How do these celebrations look different due to COVID-19?

Activity #2

Take the time to look into your area’s history with the Civil Rights Movement. Were there sit-ins in your hometown? Were there wade-ins at a beach you go to with friends or family? Find at least three examples of civil rights activism in your area and consider what the civil rights activists and local residents must have experienced or thought as part of these demonstrations.

Did you try out these activities? What are some of the ways that you can celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day with your friends, family, and community? Share your activities with us on social media by tagging History Becomes You and by using #historybecomesyou !

Check back in Thursday for the next of many peeks into history!

What an interesting story about Dr. King’s work in St. Augustine! Like you, I had never heard of his efforts in Florida before. This year, it appears that many family and community gatherings are back in full force after being cancelled or held virtually due to Covid last year. I have read about concerts, family fun activities, and parades. Our local library is sponsoring a Black History Month writing and artwork contest based on quotes from Dr. King. The quotes provided are still so relevant! One of my favorites is “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.”

LikeLike

I remain shocked that his work in St. Augustine never came up in school. I’ve even spoken to friends who went to other schools and they were surprised that it wasn’t covered in their classes either. What a great reminder that there is so much history still out there to explore!

LikeLike