In almost every community there is a place that everyone still talks about. They reminisce about their fond memories or strange events. They share their passion for a building, a bridge, or a site that formed and shaped their homes, schools, and experiences.

In almost every community there are people who, in the midst of these reminiscences and stories, still feel the pain of loss when these places change beyond recognition or are even demolished. These people recall the beauty of these lost places, the changes that they heralded for their communities, and the hard work that they put into attempts at saving these historical landscapes. These are the preservationists and community activists.

And, in one of those towns, cities, and communities, there once stood the El Vernona.

And, behind the El Vernona, stood teams of preservationists and activists trying everything in their power to save their beloved landmark.

The El Vernona

Built in the 1920s, the El Vernona was the brainchild of architect Dwight James Baum and Owen Burns – a prolific developer during the Boom years of Sarasota, Florida. Named for Burns’ late wife, Vernona Hill Freeman, the massive hotel dominated the view of Sarasota’s bayfront and signaled a shift not only in the movement of development towards the water, but also a shift in the size and opulence of local architecture.

Afterall, you can’t formally open a hotel with a grand ball and not expect the new addition to practically ooze luxury, right?

Well, the El Vernona did not disappoint.

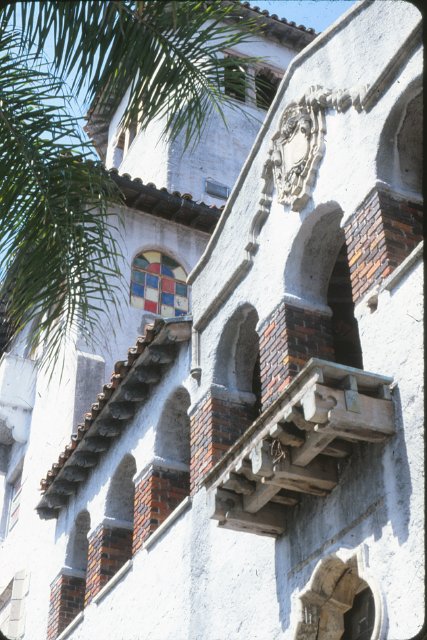

Designed in the Mediterranean Revival Style, the El Vernona offered a mixture of several architectural styles including Colonial Revival, Spanish Renaissance, and Hispano-Moresque features. It was the perfect follow-up to Baum’s first Sarasota project – John and Mable Ringling’s Ca’d’Zan (translated to mean the House of John). In fact, the two projects became so well-known that Baum’s work was even written up in a national architecture publication – “The American Architect” – in August of 1926 which praised both buildings as a new regional style of architecture which was particularly suited to Florida.

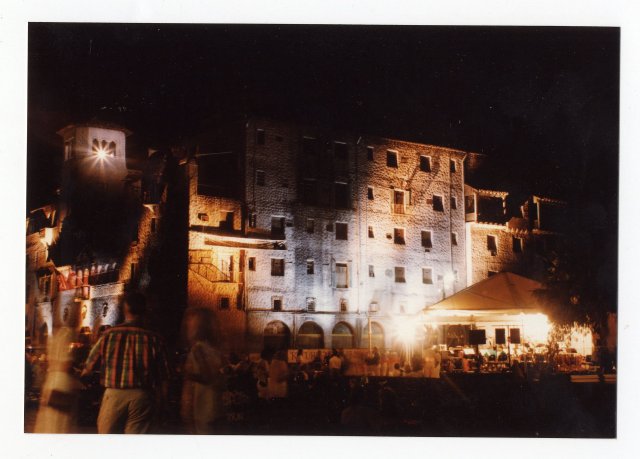

During its formal opening grand ball, attendees found themselves entering a towering structure of gold stucco and stone punctuated with dozens of wrought iron balconies and brick insets, almost stepping back into time

Unlike most grand openings, this hotel did not appear bright, new, or seamless. Instead, the El Vernona had been purposely distressed to appear historic from the start. Perhaps playing into the narrative of Spanish settlement or even the (highly inaccurate) legend of Sara de Soto – the young daughter of Hernando de Soto for whom Sarasota was supposedly named after her arrival here as part of her father’s landing party – the El Vernona stood tall as a faux relic of the past. Inside, the sheer magnificence of design could be seen in every direction. From the imported tiles that lined the walls and floors to carefully carved Spanish galleons and broad pecky cypress beams which projected from the lobby ceiling, every detail was taken into consideration. Entering the monumental dining room, complete with a central fountain and second-floor clerestory, it would have been easy to imagine the daring performances that would take place there in the future.

John Ringling Hotel and John Ringling Towers

After John Ringling’s purchase of the hotel in the 1930s, it did indeed play host to dozens of circus acts for years to come with residents remembering a powerful man on a white horse galloping up the steps and into the dining room to announce the performers. Not only had the circus come to town, but it had come to the El Vernona – now renamed the John Ringling Hotel.

After the Boom period, however, came the Great Depression and, although the hotel survived, the changes to tourism signaled difficult times for many of John Ringling’s endeavors.

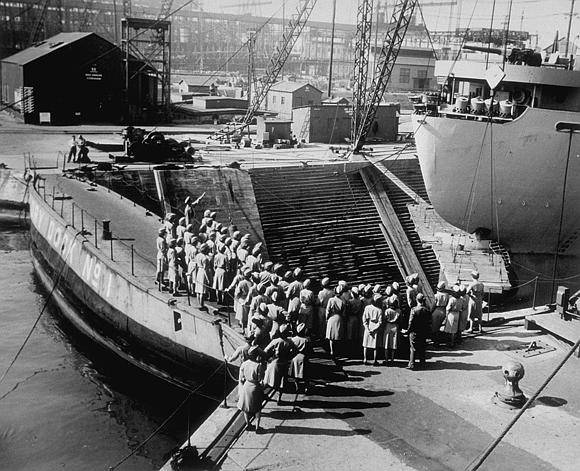

Nonetheless, the John Ringling Hotel made it out of the depression, into World War II and the arrival of military men and women to Sarasota’s shores. Yet, despite this influx of new people, the hotel fell on hard times during the 1950s and, in 1964, was converted into an apartment complex (then renamed the John Ringling Towers). But, with time and changes to building codes, the alterations (including window air conditioner units and a poorly planned elevator shaft) took away from the initial appeal and beauty of the building.

Ultimately, the stunning structure found itself vacant by 1980. Yet, rather than see its splendor turn to squalor, community activists stepped forward and threw themselves into preservation efforts with a reckless abandon.

Preservation by the People

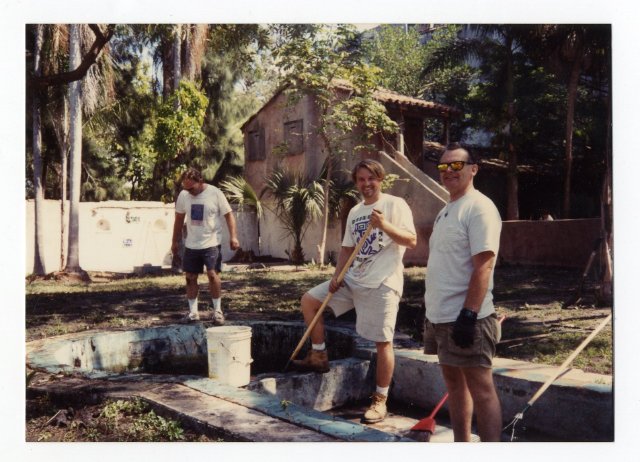

From gardening to plumbing and from fundraising to advocacy, the preservation work of local organizations and community groups was unfaltering. Determined to avoid demolition by neglect, locals organized a series of projects aimed at reminding the growing Sarasota community of what made this building and site so special. Not only had it helped to build Sarasota’s tourism industry, but the El Vernona/John Ringling Hotel/John Ringling Towers had also become a vital part of the community’s cultural landscape.

Their fears came to light when, on March 10, 1983, the Buildings Department of the City of Sarasota issued a demolition permit to the owners of the hotel and the adjacent site (including the original Burns Realty office and what had become known as the Karl Bickel house).

Fundraising and advocacy work expanded and hundreds of local community members stepped forward to protest the potential demolition.

Saved from the wrecking ball, albeit temporarily, the building remained vacant as organizations proposed countless projects to save it. Even proposing adaptive re-use of the structure and taking into consideration more modern creature comforts such as central air conditioning, the groups went before developers and local companies in the hopes that their proposals might be the saving grace of this 60-year-old structure.

It appeared as though hope was on the horizon when, in December of 1986, the owner of the site at that time (Larry D. Fuller) sent a letter to the State Department of Historical Resources indicating his interest in completing the National Register nomination for both the hotel and Bickel home. Stating that a previous owner had elected not to designate the structures, he instead requested a “reversal of objection” and started the ball rolling on officially listing the property on the National Register of Historic Places.

Listed officially in March of 1987, the buildings were celebrated not only for their association with Owen Burns, Dwight James Baum, John Ringling, and Karl Bickel but also as a sterling example of their architecture style – a true rarity among remaining structures from the Boom period.

For many in the community, a sigh of relief was felt as they hoped that this would mean the protection of the site for years to come.

But, in 1998, the wrecking ball came for the iconic site. Despite years of community resistance and preservation efforts and even its listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the hotel and Bickel home were demolished to make way for a new hotel. Gone was the building that so many adored. Gone was the site that so many had protected and tended. All that was left were the memories and documentation of their efforts which found homes in a local archive and museum.

For many, the phrase “gone but not forgotten” rings true for this landmark as preservationists and community members continue to lament the loss of the El Vernona. It is a prime example of the power of local people in preservation efforts and a call to action for many communities with similar sites throughout the country.

So, in celebration of Historic Preservation Month, History Becomes You thanks preservationists and communities all over the world who continue to fight for the protection of historic sites and structures. Your work and efforts have not gone unnoticed and we celebrate you!

If you would like to learn more about Historic Preservation Month, historic preservation, or preservation efforts in your area, you can follow #historicpreservation, #thisplacematters, and #historicproperties on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Activity #1: Most Endangered

Did you know that preservation groups announce lists of endangered sites and structures each year? One of the most widely known is the list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places which is put out by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. For the year 2022, their list includes the following sites:

- Francisco Q. Sanchez Elementary School (Humatak, Guam)

- Camp Naco (Bisbee, Arizona)

- Palmer Memorial Institute (Sedalia, North Carolina)

- Brown Chapel AME Church (Selma, Alabama)

- Minidoka National Historic Site (Jerome, Idaho)

- Picture Cave (Warren County, Missouri)

- Deborah Chapel (Hartford, Connecticut)

- The Brooks-Park Home and Studios (East Hampton, New York)

- Chicano/a/x Community Murals (Multiple Locations, Colorado)

- Jamestown (Jamestown, Virginia)

- Olivewood Cemetery (Houston, Texas)

Are any of these historic places near you? Want to learn more about these sites? You can find out more about these places, why they are historically significant, and what threats they are facing through the National Trust for Historic Preservation at savingplaces.org.

Activity #2: Historic Preservation Near You

Do you know of any historically designated sites or structures near you? For many of us, we have historically significant sites and structures very close to home (for some of you it may even be your home). Can you find three historic sites or structures that have been designated in your area?

Don’t know what to look for? Keep an eye out for historical markers and plaques discussing local, regional, and even national significance. You’ll be surprised to find how much history is in your own back yard!

Did you learn something new about historic preservation? Did you find historic sites and structures in your area? Share your activity results with us on social media by tagging History Becomes You and by using #historybecomesyou!

Check back next week for the next of many peeks into history!